We live in a world today that more and more items we buy are either intended to be disposable, or we are culturally influenced to make them disposable. In years past it was much more common to get your shoes repaired instead of buying new ones. When was the last time you went to a cobbler? I suspect many people wouldn’t even know where to find one. Readers of a certain age are probably looking up the definition of cobbler (hint: not the pie).

We buy electronics that work for a couple of years and then get tossed, sometimes ending up in African e-waste dumps, where at the risk to their health locals strip the electronics of precious metals, and burn insulated wires to get to the copper inside, released toxic fumes. Just think how many charging cables you’ve thrown out because they were worn out or just simply stopped working.

Just this week the European Parliament voted to have the EU Commission establish a single charger standard (i.e. not Apple’s Lightning) for all mobile devices. One argument they have made is that this will reduce the amount of e-waste. In the long term perhaps, but certainly not in the short term when all the billion plus Apple device users need to switch all their charging cables when they upgrade. Will that include all the devices that use micro-USB ports to charge such as the many accessories like wireless headsets and battery packs? Presumably the EU would choose USB-C as the standard. Will it include as part of their standard specifications that would prevent poorly made cables from frying one’s phone, as many current cheap USB-C cables will do? A Google engineer, Benson Leung, famously tested many USB-C cables bought on Amazon, and ended up frying his computer. What happens when USB-C is inevitably replaced by a newer better standard? Will it require the same USB-C standard for all devices, or would it allow manufacturers to differentiate (such as Apple and Intel’s Thunderbolt 3 standard that uses the USB-C connector but offers its own advantages?). Thunderbolt 3 is actually going to be the basis for USB 4, will that be allowed as part of the EU regulations? If so is the regulation just going to be for the connector shape?

Another waste factor is manufacturers who design their products not to be fixed, or not to be fixed by anyone other than them. Apple testified this past summer in US congress that consumers fixing their own phones might make mistakes or even hurt themselves, which is why they did not sell parts directly to consumers. See iFixit’s response to Apple’s testimony, to see an alternative view from one of the main companies making it possible to do repairs yourself.

John Deere has famously been making purchasers of their tractors sign software license agreements, so even though they own their tractors, since the tractor uses software, they are required to go to official John Deere repair shops to get their tractors fixed, and use official John Deere parts (which the software can recognize). John Deere even offers products that can be upgraded through software only, so even though the hardware is exactly the same, they can charge more for different capabilities. That may be acceptable in the world of software and services, but many farmers have picked two alternative options – buying used tractors that predate the software licenses, or buying hacked firmware from Eastern Europe which allows them to have their tractors fixed wherever they want, and allows them to use non-approved (and cheaper) parts.

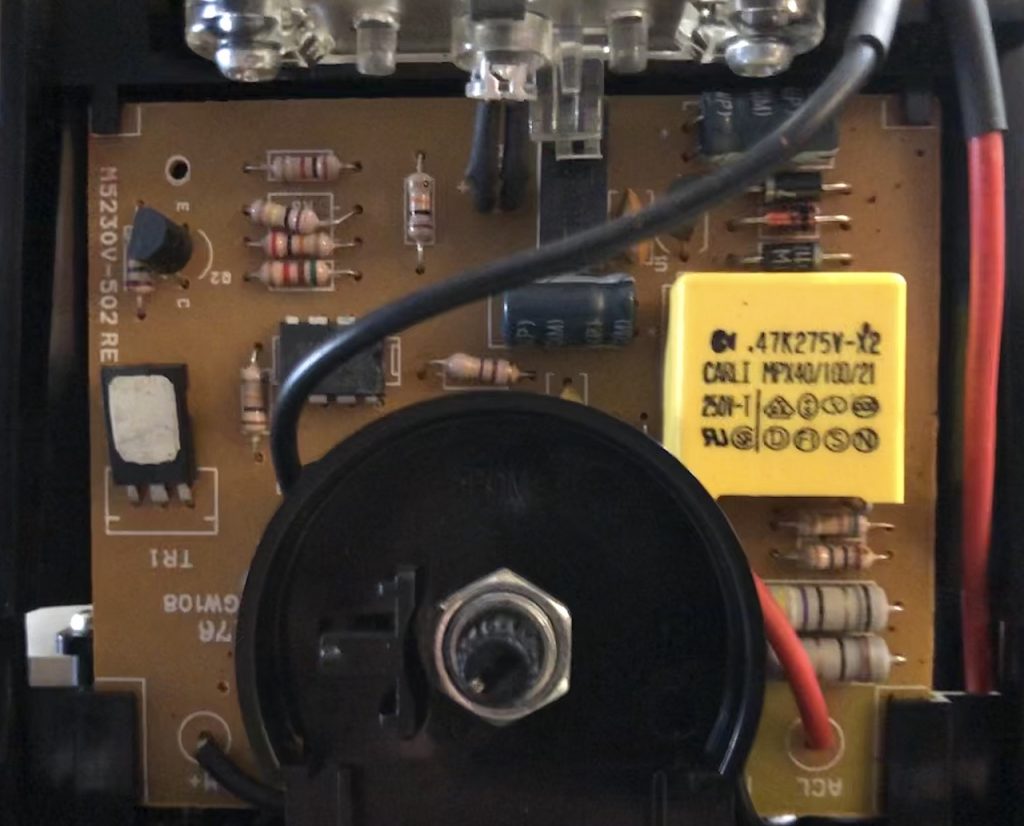

Just this week I fixed two electronic appliances in my home. The first one was a coffee grinder which had stopped working. I searched online and found several people with the same problem, that had said a particular capacitor had to be replaced. I found someone who had instructions on how to open up the grinder, checked out the specs of the capacitor inside, and ordered a replacement on eBay. Once I had the capacitor it took me about 20 minutes to desolder the old capacitor and re-solder the new one. For a few dollars and 20 minutes of work my grinder came back to life. Admittedly, if I lived in the US where the same grinder cost half as much, maybe I would have just replaced it. Additionally, if someone else had not figured out that the capacitor was the problem, I would never have even attempted it. Sure, I could get a capacitor tester and test the board, but I don’t think most people would do that, and while I might guess that was the problem, I didn’t have to in this case (and buying a capacitor tester for just this repair would not make it worthwhile).

The second appliance I fixed was my refrigerator. It’s always been amazing to me that the refrigerator my family had when I was growing up lasted decades with no problems, and today it seems like you’re lucky to buy a refrigerator that lasts 5 years without having to be fixed. Certainly today’s refrigerators have more features like ice makers and chill drawers and LCD screens that let you accurately set the temperatures of the refrigerator and freezer sections, etc. These features are driven by a computer that wasn’t needed decades ago, so there’s a lot more to break. I’ve done minor repairs to this fridge in the decade I’ve had it, like replacing broken drawers and rails, and even replacing the tube that brings in water to the ice maker. Last week we woke up to find the fridge on, but not cooling. Everything was defrosting in the freezer, and we needed to take everything out. I looked online and after reading a few posts about troubleshooting GE fridges, I noticed that while the light in the fridge was on, the LCD temperature readings were not. I figured the problem was a broken control board (the computer that controls the fridge). Some companies, like for example John Deere as mentioned above, actively prevent you from doing your own repairs. GE on the other hand not only makes parts available, but offers videos on how to fix their products yourself (see this video on how to replace the control board). Perhaps this is compensation for the fact that their products don’t last as long as they did decades ago, or maybe it’s just smart marketing for their brand. I certainly appreciate the fact that I can look up how to fix something and do it myself. I ordered the part and after receiving it, installed it in less than half an hour. Thankfully the control board was the problem, and after plugging it back in, everything worked normal again.

There’s a good chance that the control board also had a failed capacitor, and perhaps I could have replaced a capacitor instead of the whole board, saving a lot of money. I’m sure GE knows exactly which components on the board are likely to fail first, and could share that information with consumers if they wanted to. Of course, that is a much more complicated repair, and I’m still happy with the information GE does provide, but there’s always room to improve.

I bring up these repair stories because they touch on the increasingly important issue of the right to repair. Apple doesn’t want consumers to fix their phones, claiming that besides the likelihood of damaging the device, it’s also a safety issue. I agree that as their products have gotten increasingly sophisticated over the years, fewer and fewer people are able to fix them theirselves. This is partly out of Apple’s control. Certainly as they’ve continued to make their products smaller and thinner, the techniques they’ve used to cram everything into their products have made it much harder to fix them. That’s doesn’t mean Apple couldn’t do more to make their products easier to fix. I imagine many consumers would actually prefer a slightly larger phone that was easier to fix.

With computers we’ve long had the ability to upgrade things like the hard drive, memory, or add features through expansion cards and the like. Apple moved away from this ability over the years by designing smaller and smaller computers with less upgradeability. The thin iMacs trades fashion for expansion. Their extremely powerful Mac Pro line briefly offered their beautiful cylindrical model which was a powerhouse of a machine, and incredibly engineered, but didn’t offer the expansion and customization options its pro users were accustomed to, so it was killed off last year and replaced with the current model that is fully repairable and upgradeable without needing an engineering degree. The Macbook Pro, on the other hand, has been heading in the opposite direction. The keyboards on Macbook Pros used to be removable. Today if a single key is damaged, Apple has to basically replace the entire computer – and that’s Apple itself. There is no way for a consumer to do that kind of repair.

Some people might forget that Apple’s original iPhone was the first major cell phone without a replaceable battery. Until that point it was a given that you could buy extra batteries for your cell phone, not only to replace them when needed, but to have a spare available so you could swap the battery when you ran out of power. The original iPhone even had the battery soldered directly to the motherboard, making replacement difficult even for Apple authorized repair shops. Considering the original iPhone was 2G and the iPhone 3G was released the next year, chances are not too many people kept that original iPhone long enough to run into battery problems, which is probably why this wasn’t a major issue. The iPhone 3G already had a removable connector for its battery, getting rid of the need to use a soldering iron to replace the battery.

Those more technically inclined would like a way to buy Apple-branded batteries to replace themselves. Six years ago I replaced the battery in my iPhone 4S myself, using a battery I had ordered from China. I had no problems doing it, and it extended the life of my phone for a total cost of about $6. I’m not sure what Apple would have charged back then to replace the battery, but they now charge $49 for older models and $69 for newer models, although I believe these prices have come down from what they were in the past. Back then I posted on Instagram a picture of the Chinese battery I used to fix my phone:

It doesn’t always make sense to do these kinds of repairs yourself. If you have a relatively recent iPhone model that cost you $1000, then paying $69 to have the battery replaced by Apple probably is a good idea. If you have an old iPad that you only keep around for your kids to watch YouTube on, then probably not. Actually, Apple might not give you a choice soon. They’ve started adding nagging messages to your iPhone experience when you have either the battery or the screen replaced with a non-Apple part. This isn’t exactly customer-friendly. How long before the devices simply won’t work with 3rd-party parts?

On the web site of one of the many cell phone repair shops in my city, they list their prices for screen replacements, including prices for using original OEM screens or cheaper alternative parts. Interestingly for the iPhone 11 they only list a price for using an original Apple part. Is this because there isn’t yet a good alternative part available, or because of this new Apple policy? A few other interesting things can be gleaned from this list. For replacing the back of the phones that have glass backs, only alternative parts are available. For iPads, the same, no original Apple screens are offered. For Samsung Galaxy phones only original Samsung screens are offered (is it harder to get replacement parts for Samsung phones?). For Xiaomi phones, only alternative screens are offered (as a Chinese phone are replacements easier to get?).

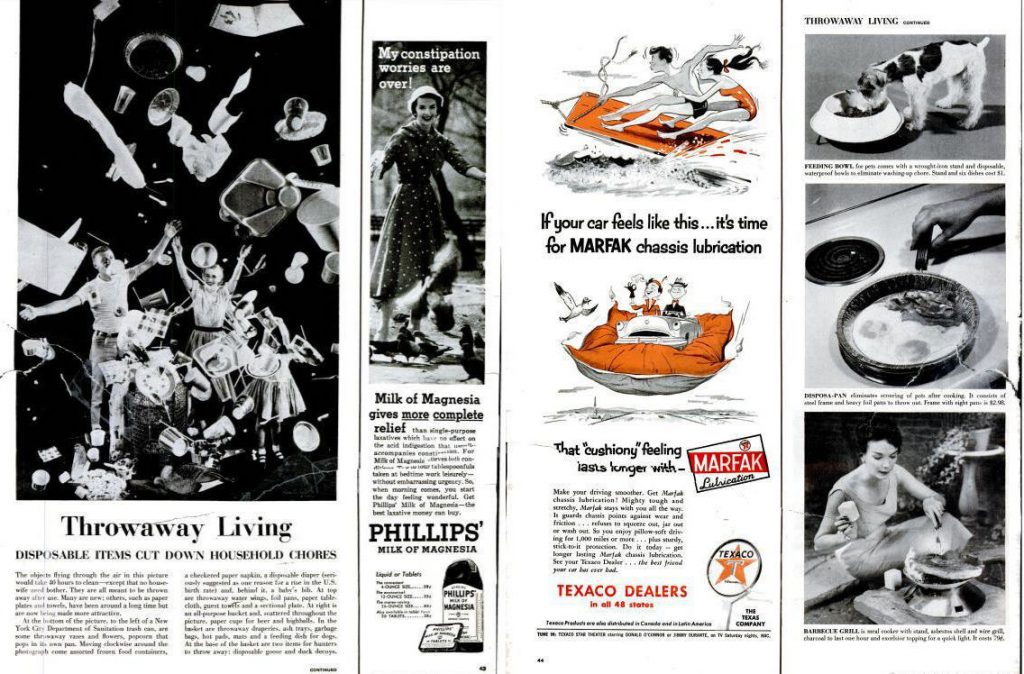

So who’s to blame for what has come to be called throwaway society? The term itself is not new by any means. A variation first showed up in 1955 in Life Magazine in and article titled Throwaway Living:

Keep in mind this same issue has advertisements for RCA’s new color TVs and Gleem toothpaste. So from 1950s consumer culture to today, have we learned anything, or are we continuing to make everything, even our electronics, throwaway items? It seems that the environmental impact of one’s product has become something many brands consider important. Are you using rare-earth metals? Does the product contain mercury, PVC, brominated flame retardants, arsenic or phthalates? What percentage of the product is made from recycled materials? Apple has a page dedicated to these questions, where you can view environmental reports on their products, such as the iPhone 11, the iMac Pro, or the Apple Watch Series 5. So if the environmental impact of a product is important to consumers (and lets be honest Apple wouldn’t be showing these reports if it wasn’t) then why isn’t repairability? Isn’t the primary reason that these environmental issues exist is because these products are ending up in landfills? Wouldn’t making cell phones easier to fix and extending their useful life have a much bigger effect on the environment? You can reduce the amount of non-recycled materials that go into a device by 5% and call it a benefit, but if the same consumer that buys that phone uses it twice as long, that’s a 100% savings.

It’s not in the interest of electronics companies (or tractor manufacturers) to extend the lives of their products. The idea of ‘planned obsolescence’ has been around for close to a century. When the automobile industry reached some level of market saturation in the 1920s, GM introduced the concept of model years to encourage people to buy newer models faster. Apple didn’t start regular annual upgrades of its products until the iPhone. About a year before the above Life Magazine article, industrial designer Brooks Stevens used the phrase ‘planned obsolescence’ in a speech, which began his association with the term (although he didn’t coin it). Some of Stevens earliest work was ironically on tractors, although he also designed motorcycles for Harley-Davidson, designed the Miller High-Life Logo, created the Oscar Meyer Wienermobile, and worked with other car companies like Studebaker, Jeep, and Excalibur. He defined the term as “Instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary.“

We, our society, need to stand up in opposition to a century of increasing planned obsolescence and a culture that encourages frequent replacement over repair. If we made it known that we were more interested in being able to replace the batteries and screens of our phones over having phones get thinner and thinner, companies would respond. We need more companies like GE that not only think about making their product repairable, but document how to do it online.

If you think it’s not possible for products like the iPhone or the Samsung Galaxy phones to be easily repairable, look at the video here from a company called Fairphone, which has a modular phone that allows you to replace individual components, even the screen, with only a simple screwdriver. Replacing the battery doesn’t even require that, you don’t need any tools. Take a look:

The Fairphone 3 shown here is clunky sure, and it doesn’t have lots of features like Face ID, multiple cameras, an edge-to-edge screen, or water-proofing. Keep in mind, however, that this is produced by a small European company with nowhere near the resources of an Apple or Samsung. Imagine what those larger companies could do if they tried to accomplish something similar. I’m against legislating this kind of change, but I’m all for making my needs known, and having the market influence companies to try to meet those needs. This modular approach could even allow an upgrade path for existing phones. Want a better camera, trade in your existing module for the newer one with more megapixels. A new OLED display instead of your older LCD display, no problem.

Right now companies like Apple and John Deere have been fighting right-to-repair legislation across the US, and around the world. While that is a problem, it’s not enough that consumers have the right to repair their own devices (that should be obvious). Truthfully I don’t think we should need right-to-repair legislation, although it does seem to be the rare regulation that decreases costs to the consumer. Companies should be designing for repair, and we should be encouraging them to do so. I can’t imagine legislating companies to make their products easier to repair, mainly because that would be too open to interpretation. We need instead to make our voices heard, let the companies whose products we use know that we want them to make their products easier to repair, and thank those that do.

Go on LinkedIn and find the CEOs of the companies that make the products you use, and send them a message, either explaining that you would appreciate it if their products were easier to repair yourself, or thanking them if they already are easy to repair. Tim Cook, the CEO of Apple, makes his e-mail address public (like Steve Jobs did before him) so send him a message. We may not convince every company to change, but some will, and the more that do will make other companies take a second look, and maybe one day all our electronic devices, appliances, and even our cars and tractors, will last longer. Instead of planned obsolescence, we’ll have planned robustness, and instead of the right to repair, we’ll have products that are designed for repair.