I was recently sent an offer to beta test a new service. The service is interesting – it is a subscription service for applications on the Mac operating system. Let me digress for a moment. Selling applications on the Mac, or any desktop operating system, has become more difficult in recent years. In the case of the Mac, this is partly Apple’s fault.

The App Store

Apple introduced the App Store for the iPhone back in 2008, and it completely turned the traditional software business on its head. Many companies made a lot of money from the App Store, and others went out of business. It messed with existing business models, and the reverberations in the software industry are still being felt. My own company, Command Speech, was founded shortly before the launch of the App Store, and it had severe effects on our business.

One of the big effects of the App Store was the race to the bottom. Traditionally, software companies had to spend money to market their applications – through magazines, newspapers, and online. There were also distribution costs. In the old days you had to pay for the media it was distributed on, whether a floppy disk or a CD-ROM, and the printed manual and box as well. You had to keep inventory. You needed to ship products, or put them in retail stores where it cost a lot of money to get shelf space. That meant you couldn’t charge too little for your app, or your acquisition cost for that customer would be more than you were getting paid. Some smaller developers could charge less, especially when the Internet brought down distribution costs, but it was still hard to get the word out. The App Store as a searchable marketplace for apps solved this problem, and allowed developers to charge less for their applications since their distribution was handled by Apple, and anyone could find their applications in the App Store. Add to that viral marketing on social networking sites, and you had the perfect storm to lower the price of software.

If you look back to the days of the Palm Pilot or Psion, the software prices were not that different than desktop software. A bit less maybe, but still in the double digits. With the App Store and viral marketing, the most common price for apps shot quickly to the lowest possible price, $0.99, if not free. It’s rare to find software in the App Store more than $9.99, and the only software I’ve seen in that category are apps that work with expensive desktop apps or with hardware, and can charge $14.99 or $19.99 because if you’re a captive user of their other product, you will pay to have a compatible mobile app.

The best example of this that I’ve seen was when Nuvo introduced a mobile app for their home music system. Nuvo has a great system that distributes music to multiple rooms, offers in-wall touch-screen controllers, and has a music server that can stream audio from its hard drive or from various online streaming services. Besides the in-wall touch screen controllers, they also offered a wireless touchscreen remote for hundreds of dollars. When they introduced their iPhone app, they knew they would be cannibalizing the sales of their touchscreen remote, so they priced the app at a price that probably made them more money than the remote – $99. I don’t know how long they kept the price that high, but I can tell you that they now give the app away for free. In fact, the great majority of apps in the App Store are free. Instead of selling the apps upfront, most developers have come up with other business models, such as in-app advertising. Advertising on the desktop has never been very popular, however, so apps on the Mac needed a different model.

The Mac App Store

In 2011, Apple launched the Mac App Store, bringing the same model of app sales to the desktop, except with one major difference. On iOS, Apple controlled all apps that were made available on the device. The only way to get your software on an iPhone or iPad was through the Apple-controlled App Store (without hacking the phone which most people would not do). On the Mac, Apple didn’t close access to the computer, so developers could choose to continue selling directly, could switch to the Mac App Store, or could try some combination.

At first, the Mac App Store seemed great to developers, particularly smaller developers. Basically free distribution, people could find you by doing a search, and updates were automatically pushed out to users. Of course there was a 30% cut for Apple, but other distribution methods were not free, and meant dealing with credit cards, refunds, issuing serial numbers, etc. The App Store simplified everything. At the beginning the App Store was missing a few things, but developers figured Apple would get around to fixing the missing features. One missing feature was a way to do a paid upgrade. Upgrades are the lifeblood of the software industry. You get a customer, they like your software, you spend time to improve the software, and you get paid for that work. Except for reasons that are still not clear, Apple’s decision not to include an upgrade route was not a missing feature, it was by design. Another missing capability for most developers was a way to do a free trial. Developers can of course create another version that users can download from their web site, but that kind of defeats the purpose of selling through the App Store.

Apple has still not added the ability to do a real upgrade. Some companies have gotten creative, by introducing a new app with a new version number, and offering it for less for the first few weeks to allow people to ‘upgrade’ and then raising the price before publicizing the software. This is an imperfect solution to be sure. The worst part is that if a user doesn’t upgrade in the set period, they cannot get the upgrade price in the future. Other developers have come up with more sophisticated solutions.

Omni Group, a long-time Mac developer, has created a way to do both free trials and upgrades, although it’s a bit complicated. They’ve started to make their apps free on the store, enabling for a free trial. After a couple of weeks, features in the app are disabled unless you purchase them through an in-app purchase. If you want to upgrade, you can find the old version of the app on your hard drive, and it will verify that it’s a valid version of the app, and then show you less expensive in-app purchases to get the same features. Not particularly elegant, but still workable.

There were other problems with the App Store, including additional security features (sandboxing in particular) which prevented some developers from selling through the App Store. Other developers found the effort too complicated, and reduced their interaction with their customers, and so abandoned it. Even so, the world for Mac software was changed. Prices had come down and they were not going back up just because an app was not in the App Store.

Loss of Marketing Avenues

In the old days there were magazines and web sites focused on the Mac, but even the web sites slowly started shutting down. Back in 1997, MacUser magazine in the US merged into MacWorld Magazine. MacWorld shut down its printed magazine in 2014. MacUser UK closed down its magazine in 2015. The MacMinute web site, a popular mac news site shut down in 2008 after the death of its owner. MacLife.com, the web site of MacLife magazine merged into the generic TechRadar site in 2015. Is there still a magazine? I have no idea. MacNN, another popular Mac news site shut down in 2016.

Bundles

In 2006, a new style of software marketing was introduced – the bundle. MacHeist pioneered this marketing scheme, where multiple software products were bundled together and sold for a low price. The site gamified the process, adding challenges that could get the user additional software. The site also raised money for charity at the same time.

Controversial at the time, since relatively little money went to the developers themselves, the developers looked at it a bit differently. They looked at it as a way to gain new customers, who they would get more money from through future upgrades. MacHeist marketing its bundle as a limited time event, generating lots of sales over a short period of time. This model was copied by many other companies, generating all kinds of bundle sites such as BundleHunt, BundleFox, StackSocial, FairBundle, and more. Many sites came and went, such as Bundleecious, MacBundleBox, TheMacBundles, etc. How many bundle sites could operate at the same time?

Deal Sites

Another variation on the short-term deal are the individual deal sites. They offer a discount on one or more apps separately for a day or a week. Some sites of note include MacZOT and MacUpdate Promos, which is a directory of Mac software that also offer deals on a regular basis.

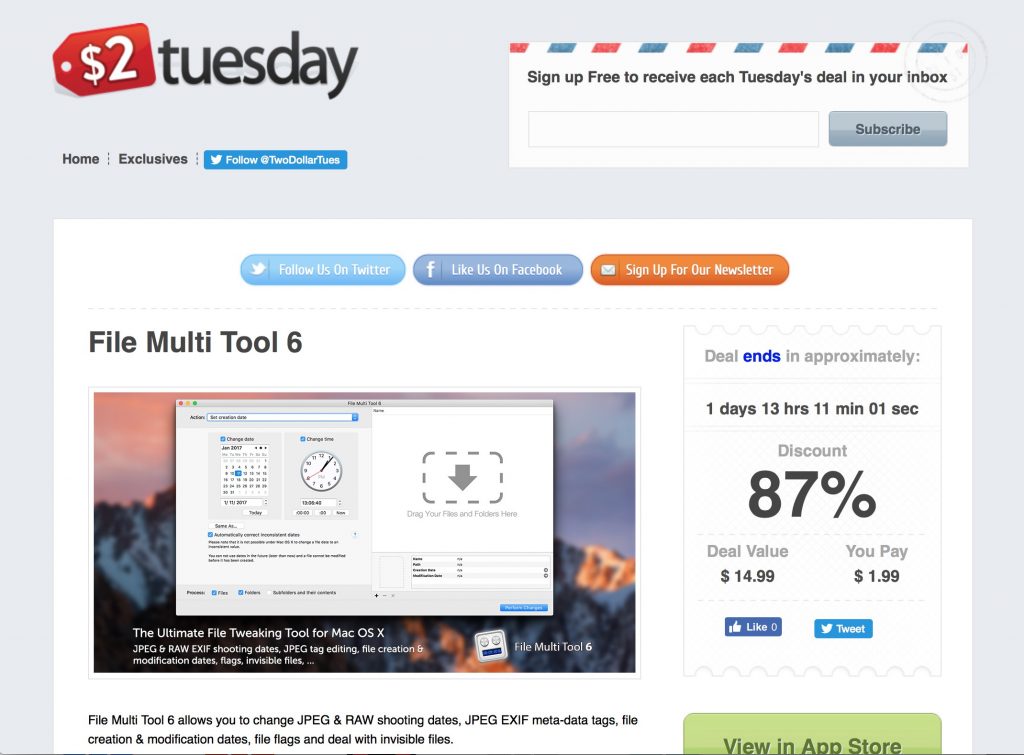

Besides the lack of immediate payback from bundle sites, another downside is that it precludes selling through the Mac App Store. Of course, not every developer wants to sell through the Mac App Store, but if you could properly promote your app, even at a big discount, it would help your rankings in the store, and make your app more visible, which would bring in more sales, etc. A beneficial cycle. One site that targets this opportunity is Two Dollar Tuesday, a site that promotes discounts on apps, but which sends you to the Mac App Store to make those purchases.

Two Dollar Tuesday markets the discount (if an app is normally $9.99 then they market it as 80% off) to their subscribers and the developer lowers the price of the app in the app store for the period of the discount (up to a week usually). Like MacZot, the site is essentially a large mailing list that allows software publishers to reach a large number of targeted customers. Another site that follows a similar model is MacAppStoreSale.

A Subscription Model

So back to the beta service. The service is called SetApp, and offers a large number of Mac applications (currently 60 and new ones have been added over time) for a set monthly subscription price of $9.99/month. I was sent an invite from a software publisher whose application I’ve already paid for, whose application is one of the applications in the subscription. Of course, that’s a bit of the problem. I already own many of the applications I like in the subscription.

Here are the 61 applications currently in the subscription:

| Aeon Timeline | Get Backup Pro | Permute |

| Alternote | Gifox | Pixa |

| Archiver | GoodTask | Polarr |

| Base | HazeOver | RapidWeaver |

| Be Focused | Home Inventory | Remote Mouse |

| Blogo | Hype | Renamer |

| Capto | iFlicks | Screens |

| Chronicle | Image2icon | Shimo |

| ChronoSync Express | iMazing | Simon |

| CleanMyMac | iStat Menus | Sip |

| Cloud Outliner | iThoughtsX | SQLPro Studio |

| CodeRunner | Jump Desktop | Squash |

| Disk Drill | Lacona | Studies |

| Downie | Manuscripts | TaskPaper |

| Elmedia Player | Marked | Timing |

| Findings | MoneyWiz | Ulysses |

| Flume | My Wonderful Days | WiFi Explorer |

| Focused | Numi | XMind |

| Folx | Pagico | Yummy FTP Pro |

| Forecast Bar | Paste | |

| Gemini | PDF Squeezer |

The service installs a folder on your hard drive with all the applications, except they’re not really the applications. The first time you launch one of them, it shows a preview of the application with a screenshot and a description, and if you want to use it you then have it installed remotely. The next time you launch the application, it launches normally. It’s a nice solution that both gives you a way to find out about the applications, and removes the need to store applications on your hard drive that you’re not using.

For me, since I already own most of the applications I want to use, I need to calculate if the $120/year is worth it for the applications I don’t own. That depends on how many of those other applications I want to use. Sure, if I subscribe to the service I won’t have to pay upgrade fees for the applications I do own. That requires a more complicated cost/benefit calculation. In general I’m opposed to software subscriptions, such as Adobe Creative Cloud. I particularly don’t like the idea of software stopping to work when I stop paying, and I can’t stand the massive number of Internet calls these subscription apps seem to make back to their servers. Try installing a single Adobe CC app with a network monitoring tool such as Little Snitch, and you’ll be shocked how often and to how many servers that single app tries to phone home.

That’s the case where there are no other options. Adobe gets away with that because there are not many alternatives to many of their applications. There’s nothing yet to indicate that these software publishers are planning to use this subscription as their only means of distribution. I suspect that wouldn’t make sense for most of them. As such, as an additional option, it’s probably a good thing. Someone should probably put together a chart showing the cost of each of these applications, and the upgrade costs over the last few versions, to let someone see if they would be paying over $120/year in upgrade fees on the apps they want.

In a world where many of the most ubiquitous desktop applications are available through the web, such as office suites (Microsoft Office 365 and Google Docs) and photo editors (Adobe Photoshop Express, Fotor, Pixlr), it seems logical that even non-web-based applications would find a way to get into the subscription model. For SetApp, I suppose the big question is does their mix of applications appeal to enough people and provide a big enough payoff to the developers who include their applications in the subscription. The beta ends in March, and it will be interesting to see how many people make the shift to paying $9.99/month. I don’t expect they would be promoting their numbers, at least not right away, but I suppose a good proxy for that information will be if new developers continue to add their apps to the subscription in the months that follow.