“When I was a kid” is the beginning of many a discussion on how things were better in past generations. Obviously, obviously, it was better to play outside than to watch television. The effects of technology on people, such as how using social media affects our brains is a common discussion point today. Are we living in a bubble or echo chamber? These are all interesting perspectives on the effect of new technology on our brains, but there’s a more physically visible effect of technology on our lives, and perhaps it illustrates similar effects.

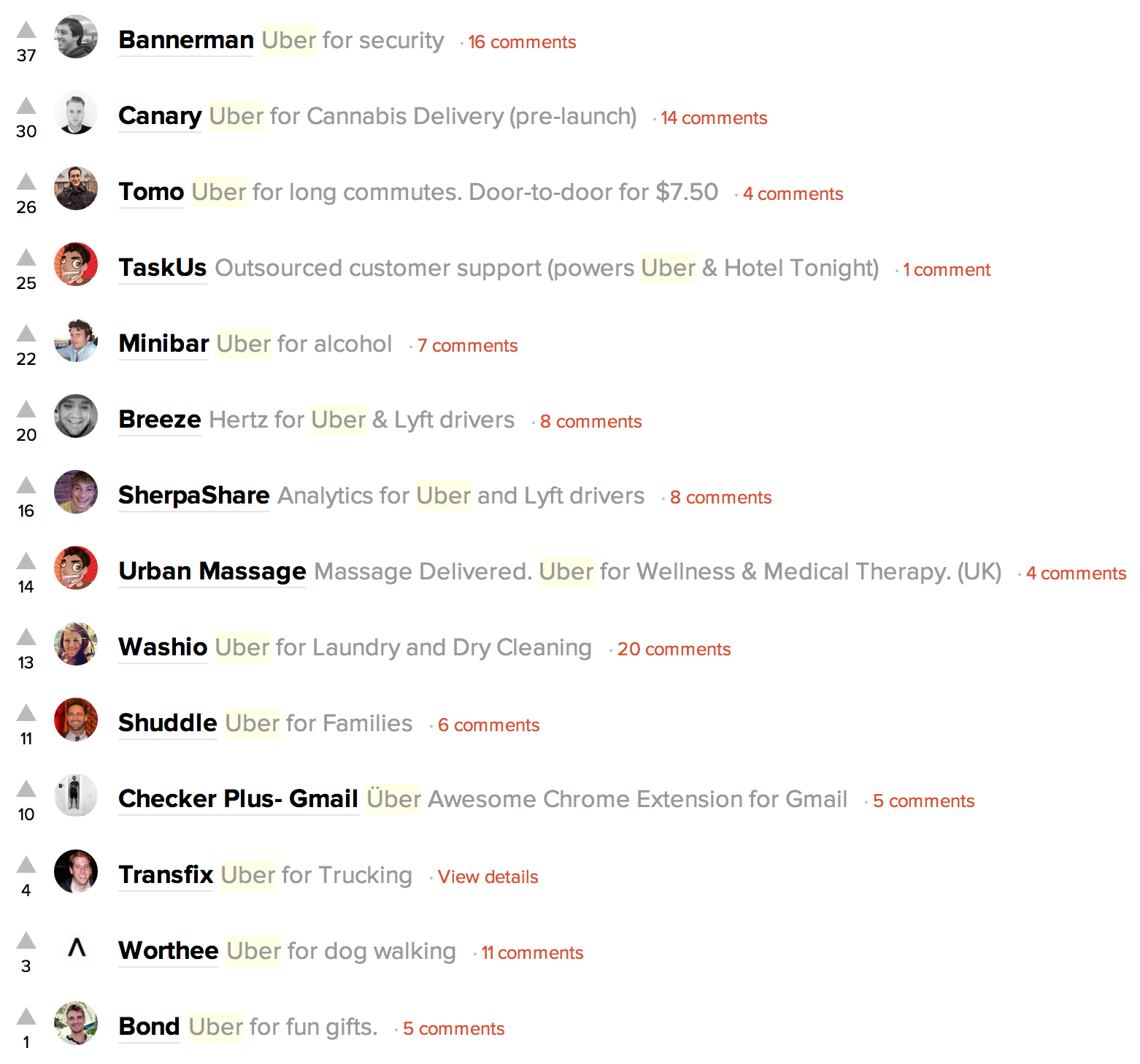

One of the biggest categories of tech companies getting funded these days is transportation. Uber‘s $72 billion valuation may grab the headlines, but other companies like Lyft, Didi, Grab, Ola, Gett, and Go-Jek are all valued over a billion dollars and targeting the ride-hailing/taxi space. As an aside I wrote of the tendency of companies to compare themselves to Uber back when Uber was only an $18 billion company in Uber meets Pretty Woman. For anyone who lives in an area underserved by public transportation and/or taxi service, these ride hailing services have made many people’s lives easier. One can argue if the lives of the drivers have been improved. Certainly for many it has been a great opportunity to get an income stream they wouldn’t have otherwise.

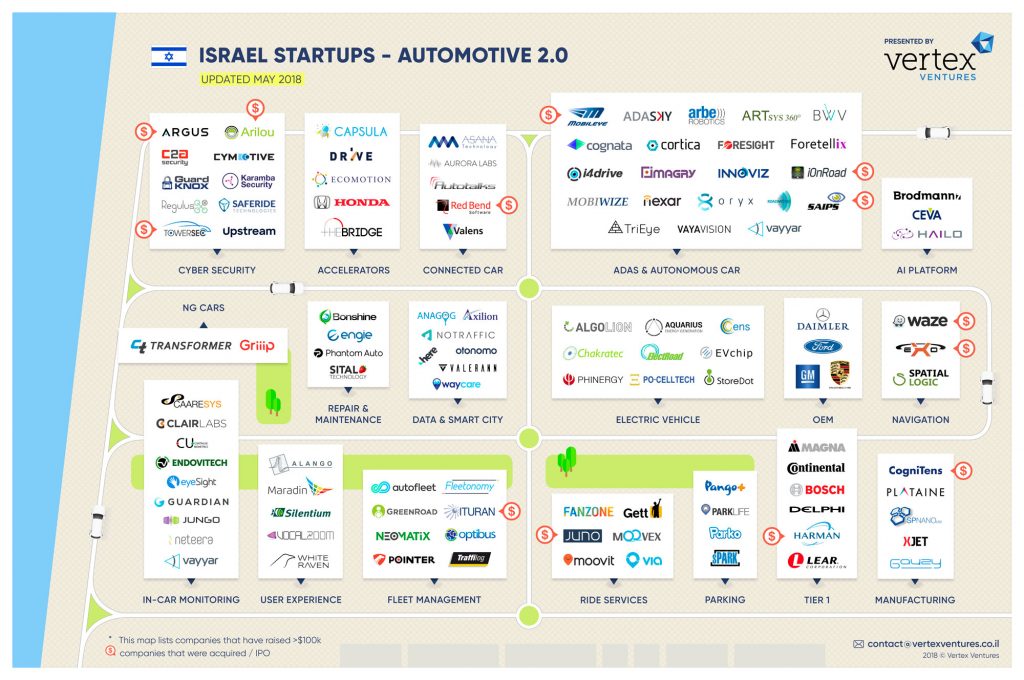

In the end, there is no question the goal for many of these companies is to offer autonomous cars without drivers. Uber for one has invested heavily in this technology, and even in technology for flying taxis. As an example of how complicated this field has gotten, here’s a map of just the companies in the automotive technology space that were founded in Israel:

All of this sounds a lot like progress. Of course progress has sometimes been mocked and Bloom County and Big Yellow Taxi come to mind (in that order since Big Yellow Taxi came out before I was born, although Bloom County also dates me these days). I’m not one to mock real progress, but what some people think is progress sometimes leads us backwards. In terms of transportation, induced demand comes to mind. Induced demand is the concept that when supply increases, consumption also increases. In terms of supply and demand it’s fairly easily to figure this out. Increasing supply generally reduces cost, thus increasing demand for a product. When we look at transportation, our first instinct is to throw out this insight. If you have a highway that is congested, obviously adding lanes to the highway will reduce traffic. Except, in almost all cases, it doesn’t. To look at the supply and demand model again, you are increasing supply and thus reducing the cost of traveling. If driving on a two-lane highway is frustrating it may convince you not to go to the places that highway took you, so you stayed at home. Now that it’s a four-lane highway, you head out and fill the road just as much as it was before.

We don’t think of adding lanes to a highway as a technological advance, although at one point it certainly was. Road-building using a form of concrete (still superior to modern concrete in many ways) is the technology that allowed the Roman Empire to expand from Iraq to England. Today we think of ride-hailing apps, crowd-sourced navigation, electric cars, and autonomous driverless cars as transportation technology, but will these technologies do what they intend, or like adding lanes to highways will we find ourselves stuck in traffic again?

Take the ride-hailing apps. At the beginning one of the arguments for ride-hailing apps was that they would reduce the number of cars on the road. However, so many people find hailing an Uber to be more convenient than the alternatives that the use of the subway in New York is actually in decline. The number of cars on the road in New York is actually higher since Uber entered the market, and the amount of traffic has increased.

The number of taxis on the road in New York used to be limited (somewhere around 13,000), and in any case difficult to change due to the massive costs of purchasing a taxi medallion (medallion prices peaked at $1.3 million right before ride-hailing services entered the market). Today New York City taxi medallions are probably worth a quarter of their peak, and in some places the prices are worth a tenth of what they once were. I don’t have a problem with the plummeting costs of medallions as they were always an artificial constriction of commerce by local governments, and essentially taxed the drivers to the point of not being able to make a living. That said, no one who supports ride-hailing services would tell you that the increase in traffic is a good thing for the cities where this has happened. This is without even looking at the problems of safety that has arisen in the less-regulated world of ride-hailing services. Driverless cars may solve the safety issue, but they won’t solve the traffic issue.

Waze was also an attempt to solve the traffic issue, but for all the benefits of Waze, I don’t think they would claim they’ve reduced traffic congestion. Waze’s slogan is “Outsmarting traffic, together.” Waze is great at re-routing cars around major traffic jams caused by accidents, but of course it reroutes lots of cars, and sometimes to places that are not used to having a lot of traffic. It’s an odd feeling when you’re driving using Waze, and you find it directing you to an exit and you notice that everyone else is also heading for the same exit. Living in the country that probably has the highest penetration of Waze users (I’ve heard half of all drivers use Waze here), this odd feeling is fairly common. Of course Waze isn’t perfect, and famously directed traffic toward a highway that was flooded in 2013, because it detected that there was no traffic on the highway. More significant, however, is figuring out if using Waze makes it easier to get somewhere, thus lowering the overall experience cost of travel and increasing demand. Does the very fact that Waze exists increase traffic congestion?

Again putting aside the safety issue (such as the drivers and pedestrians killed in testing), I think it’s worth taking a look at the effect of driverless cars as well. Let’s say in a few years everyone starts buying autonomous cars that drive them to work. It sounds great. I can nap, or work on my presentation, or whatever. My car can drop me off where I work, and maybe even go park itself in a lot. At that point it sits idle until I’m ready to leave. Maybe it could go further to a cheaper parking lot and save me some money. Since it’s going further away it’s spending more time on the road and causing more congestion. It could in theory even go all the way back to my house and park in my driveway. Depending on how far away I live from work, that might even be cheaper. It would mean doubling the time on the road, however, and causing even more traffic. Maybe the car wouldn’t be idle the whole time. Maybe instead of my children taking a bus or walking home, the car could go pick up my children from school and drop them off at the house (or at a friend’s house). The car could then wait until it predicted it needed to leave to pick me up, and would then come and get me at just the right time. All of this is way out in the future, but it brings up some interesting issues. How would autonomous cars help reduce the number of cars on the road? Would they? If the only difference is that you can now get work done in the car, then might that not increase the number of cars on the road? Would the temptation to use those cars when they would have been idle before cause even more congestion?

If the goal is to reduce the number of cars on the road, and make transportation more efficient, then the approach of companies like Via could be considered as moving in the right direction. Via is a ride-hailing app that focuses on ride-sharing. The whole idea is to get multiple people in the vehicle and being efficient in getting people where they’re going. Via’s slogan is “We Ride Together.” Interestingly, while Via is pushing their own branded service in several cities, they are also working with other companies to roll out their own services based on Via’s technology. It makes sense that a lot of the companies Via is talking to are Bus companies. You can think of Via as a way for bus companies to offer bus routes that are customized exactly to their customers.

Looking even further to the future, if Uber and other companies like Terrafugia, EHANG, Cartivator, AeroMobil, Zee.Aero, Kittyhawk, and Vahana can get their vehicles into the sky, what happens with traffic in the sky? Add to this the large number of companies such as Amazon that are looking to delivery products via drone, and the traffic below starts looking a lot easier to manage than the traffic above.

When drone companies start sending packages all through the skies, they will certainly have systems in place to manage the locations of all of their drones, but what about everyone else’s drones? There’s no way that the existing air traffic control system could manage flying cars (let alone smaller delivery drones), so something a lot more automated would be needed. Would any of these cars even allow passengers to fly them directly? Probably not. Will cities (or states or countries) need to develop their own technological systems for urban air traffic control? Will delivery drones stake out a specific altitude, while passenger cars go at another higher altitude? What happens when a vehicle goes outside of the allowed altitude? Will there be any liability for a passenger of a flying car that they don’t directly control? Is the car company liable if something goes wrong? Is the city liable if their air traffic system doesn’t work? I imagine no city is going to allow themselves to be liable, so it falls to the car manufacturer, or service provider (which could be the same company), or the individual. If the individual ends up not being liable, then that would leave to manufacturer or service provider. How many accidents before companies start dropping out of the space, however? Would those companies be protected to insure the technology progressed? Would the government take over the technology as the only entity that could legislate its own immunity?

These are all complicated issues. Not many of these technologies seem to actually reduce traffic congestion, even if almost all of them start out with that goal. Improving public transportation seems key to finding a solution, but with public transportation usage dropping with the addition of ride-hailing apps and other technology, it seems even harder to improve public transportation networks. Maybe public-private partnerships like those behind adding systems like the Hyperloop and other above-ground pod-based personal transportation systems for local transportation might be part of the solution. Developing last-mile solutions is also an important piece of the puzzle. When I lived in New York I walked out my door and I was a block away from the subway. Today I’m at least a half hour walk from the train station. I could take a bus to the station, but I wouldn’t consider it reliable enough to insure I made it to a train on time. Getting to the train on time is important, and getting from the train to an office on the other side is also important.

It’s not a coincidence that almost every ride-hailing company mentioned above has either rolled out their own bike sharing service, or purchased one. Uber bought Jump, Lyft has been circling Motivate, Grab launched GrabCycle, and Didi bailed out Bluegogo and invested in Ofo, and then integrated them both into its app. Other solutions to the last mile are also being worked on, including electric scooters – just look at the twelve companies that have applied for five spots in the two-year San Francisco scooter trial. It shouldn’t surprise anyone that Uber and Lyft are among those twelve.

So here we are on the precipice of a revolution in transportation. Let’s just hope it doesn’t look a lot like it has for the past century. If we’re all sitting in traffic in a decade, I think we’ll all be disappointed at the loss of potential.