Eggs are an indispensable part of the global food market. Not just for that omelette you had for breakfast, eggs have many roles in baking, cosmetics, and in the production of medicines and vaccines. Somewhere north of 1.5 trillion eggs are produced each year. There are many varieties of chickens out there, but the eggs you buy in the store come from very specific breeds. What’s most important to understand is the separation between broiler and layer breeds. Broilers are chickens raised to be sold for their meat. They grow quickly with less feed, and have more meat on them than layers. Layers are smaller chickens that are bred to produce large numbers of eggs. They do not grow as quickly and don’t have a lot of meat on them, but they do produce more eggs with less feed. Note that in both cases, the breeds are geared towards the highest efficiency for their purpose.

Only about half a percent of all eggs produced worldwide go towards producing new layer chickens. That’s about 8 billion eggs per year. The dirty little secret that farmers don’t want to talk about, is that less than half of those eggs become adult layer chickens. Why less than half? Some eggs are infertile and never hatch. That makes up to 15% of eggs. However, eggs split evenly by gender, and male layers have no purpose. Male layer chickens obviously can’t lay eggs, and they also don’t have enough meat or grow efficiently enough to be sellable as meat. Layer eggs hatch, and are checked by human ‘sexers’ who separate the desired female chicks from the undesired male ones. The male chicks are then culled. That’s a nice way of saying that roughly 4 billion male layer chicks a year are killed right after being hatched.

No one would look at this practice as desirable, least of all the farmers who wasted the resources to produce the eggs, incubate them for three weeks, and then paid for people to separate and kill them. That’s without even looking at the ethical issues involved.

Possible Solutions

So what solutions are there to prevent the culling of 4 billion male chicks every year? Let’s take a look at a few of the options.

- The best solution would probably be to create a new breed that could be used as both a broiler and a layer, i.e. a breed of chicken that both had a lot of meat, but could also produce a lot of eggs. This might be ideal, but is nowhere near close to being achieved. It probably can never be fully achieved, where a single breed could have as much meat as current broiler breeds, and also produce as many eggs as current layer breeds.

- In theory, the next best solution would be a layer breed that only produced female eggs. I’m not sure such a thing would be possible, but if it was, it would probably require gene-editing, which makes it less ideal (see below).

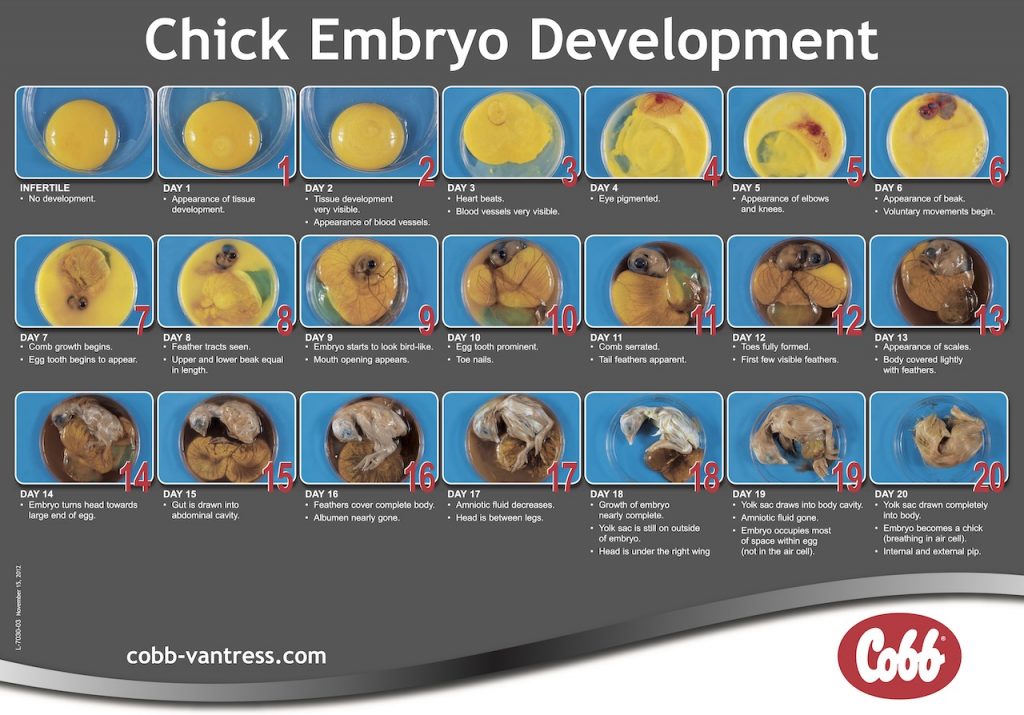

- The actual next best solution would be to determine the sex of the egg before hatching. Ideally, one would determine the sex of the egg even before incubation. Once you start the three-week incubation process, you run into additional problems. First, you’re using additional resources to incubate an egg that you don’t want. In an egg, the heart starts beating only a few days after incubation begins. In the industry it’s generally considered that the chicks in the eggs become sentient around day 10. Thus, for in-ivo (in the egg) sexing, the industry is trying to determine sex as early as possible, and strongly desire it to be done no later than day 9. That is turning out to be quite difficult. Different technologies are being used, some that analyze the eggs using spectrography, some do endocrinological analysis of the fluid inside the egg, and some use gene-editing to make the different genders determinable. An advantage of gene-editing is that it can be 100% accurate. Other solutions have not reached 100% accuracy, and thus still require more resources to clear out the percentage of mistakenly sexed chicks. Gene-edited animals, however, raise additional questions, and are banned in most countries for the time being. Whether consumers will accept genetically modified eggs (or even non-GMO eggs born from a GMO hen) is another question.

- One option which is being tested in some countries in Europe is simply raising the male layer chicks. This sounds great, but there is no way to do this economically. Farmers have no interest in paying for the feed and other resources needed to raise male layers, and there is little market for them when they reach maturity. This is mostly virtue-signaling, and while it can be done on a small scale, it is not a solution for 4 billion chicks a year.

- The last solution isn’t actually a solution to this problem, but a replacement for eggs altogether. There are a number of companies working on plant-based replacements for eggs. This won’t end male layer culling in the existing industry, but might lower the number of eggs needed globally, which would lower the amount of chicks being culled. These replacements tend to focus on specific markets, such as baking, instead of being general purpose replacements. Some companies already provide bottles of egg-replacement liquid that allow home chefs to make plant-based omelettes.

Factors in gender-determination

Multi-purpose breeds are likely out of reach for now, raising male layers is not economical, and egg-replacements will take decades to be able to scale up to anywhere near the trillion-plus eggs consumed every year. That leaves us with one primary solution, which is determining the gender of the eggs before hatching. Moreover, I would argue that only solutions that work pre-incubation can scale. Let’s take a look at the relevant factors in evaluating gender-determination techniques.

- Accuracy – What percentage of eggs are correctly sexed? How many male chicks are hatched?

- Time – When can the egg be analyzed? Pre-incubation? If not, what day of incubation?

- Speed – How long does the test take per egg?

- Cost – How much does the test cost per egg?

- Color – Does it work with both White and Brown eggs?

- Non-Invasive – Is the test non-invasive? Is it necessary to puncture the egg to do the test?

- Infertility detection – Can the technique also determine infertile eggs?

Let’s take a look that these one at a time.

Accuracy – If the technique is not a 100% accurate, then some male chicks will still be hatched. That means you will still need to sex the chicks after hatching, and will likely still need to cull them. Most government rules that being put into place are aiming for at least 98% accuracy. If fully implemented, that would still mean 80 million culled chicks a year. That’s certainly an improvement, but from a financial point of view, farmers would still need to keep a lot of their current infrastructure for post-hatch sexing and culling in place. Thus we really want to aim for 100% accuracy.

Time – Most government rules being put in place seek to have the gender determined before day 10 of incubation, since that is considered the day the chicken embryo reaches sentience. Therefore, ending the incubation of male eggs past day 9, while perhaps more humane than letting them hatch and killing them shortly after, is still a major problem. It’s also costly to take up that room in the incubator, and there are less options for use of the male eggs at that point. Ideally then the gender would be determined before incubation. That would reduce costs, and enable the most potential uses for the male eggs.

Speed – Large egg production facilities process tens of thousands of eggs per day. If the process to determine gender is too slow to keep up with this process, it’s essentially useless.

Cost – There are different grades of eggs, and one can find cage-free, free-range, and organic eggs. At the end of the day, however, most people simply buy the cheapest eggs they can find in their local supermarket. That means the cost of determining the sex of eggs needs to be kept very low. Luckily, there is already a cost involved in the sexing and culling of 4 billion eggs each year, so there may even be an opportunity to reduce costs with gender determination. Any technique that raises the costs significantly can’t be used. Techniques that use expensive equipment like MRI machines won’t scale beyond the largest of egg processors.

Color – Commercial table eggs some in White and Brown varieties. The first commercially available sexing technique only worked with Brown eggs. To be viable, the technique needs to work with all eggs.

Non-invasive – Ideally the process would work without needing to make an opening in the egg. Needing to puncture the egg creates opportunities for the egg to become contaminated with bacteria. While it’s not necessary to be non-invasive, it is preferred.

Infertility detection – While this is a different metric, and doesn’t have the same ethical problems as culling male chicks, being able to identify infertile eggs at the same time helps reduce costs for the farmer.

What’s available now

The only commercially available in-ovo sexed eggs are marketed as Respeggt eggs, “free of Chick Culling”. These eggs are marketed in Germany, France, Switzerland and the Netherlands, and priced at a premium, similar to how organic eggs are sold. Respeggt uses technology from the German company Seleggt to do their in-ovo sexing, based on an endocrinological analysis of fluids extracted from the eggs on the ninth day of incubation. While they originally used needles to extract the liquid, that proved problematic because they needed to sterilize the needles between uses. They now use a laser to make a hole in the egg, and then use air pressure to force some liquid out of the egg. This is more sanitary as nothing actually enters the egg itself. While still invasive, it is lower risk than using a needle for extraction.

Respeggt also claims to raise male layers to adulthood, even though it takes considerably longer to raise a male layer chicken than it does a broiler, and even then the commercial usage is limited. They promise the male layer is used commercially for its meat, which means it is probably used in packaged products that contain chicken meat. This is necessary since their process is not 100% accurate. Right now their claim is it is 99% accurate. That’s very good, but it still means some male layers will be hatched. With 99% of the male eggs sorted out on the 9th day of incubation, and the remaining 1% raised to maturation, Respeggt can thus claim their eggs are “free of Chick Culling”.

What’s coming?

Unfortunately, the Seleggt process as it is now cannot be used as a widespread solution, as it is too costly. It’s fine for a niche premium offering, but it won’t scale to the 8 billion eggs used each year to raise laying hens. In order to do that, you want to see something that works the same day the eggs are produced, and is 100% accurate. Of the more than a dozen companies (in addition to many universities) working on a solution to this problem, only four that I’m aware of promise either of these two metrics. Two of them use gene-editing, and two of them use advanced forms of spectrography. Note that none of these companies have commercially deployed systems yet. Let’s take a look at them.

Eggxyt & Poultry by Huminn

Two Israeli companies are approaching this problem through the use of gene editing.

Eggxyt, based in Jerusalem, inserts a gene into the male sex genome, causing male eggs to fluoresce when exposed to a special light. This works on the first day, and should be 100% accurate. Male eggs are thus easily identifiable, and can be removed before incubation.

Poultry by Huminn (formerly NRS Poultry), based in Tel Aviv, similarly inserts a gene that expressed only in male eggs, and it forces male eggs to stop development very early. Thus existing techniques for sorting out infertile eggs can be used to remove the male eggs, and no culling will be necessary.

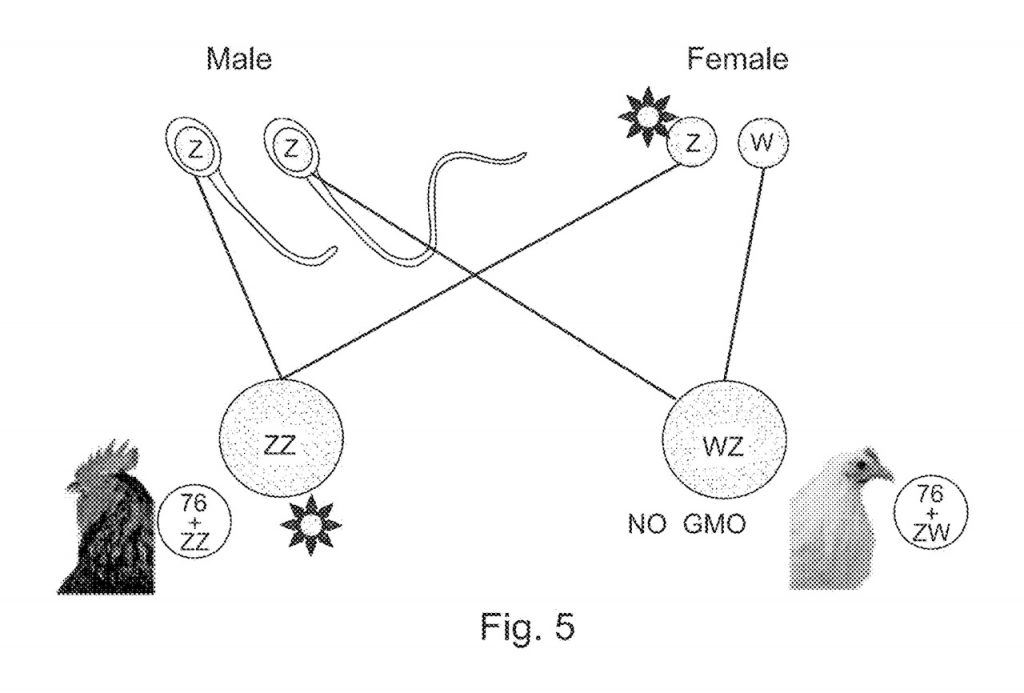

Both companies point out that while the male eggs do contain a small amount of foreign DNA, the eggs that go on to be female layers and thus are part of the food chain, contain no modified DNA. This is because the DNA that is modified only makes its way into the male eggs. Without going into a lengthy explanation of avian genetics, unlike in humans, bird gender is determined by the female. Female birds contain Z and W sex genes, and when they pass on the Z gene it combines with one of the male’s Z genes, creating a male. When the female contributes a W gene, the resulting egg becomes a female. Thus, by modifying the Z gene in a female bird, you can pass genes only onto males.

While the techniques used by these companies should be 100% accurate, the use of gene-editing raises regulatory questions that are difficult to predict. Even if the companies can pass regulatory scrutiny, it’s not clear that the market will accept eggs that come from genetically modified organisms, even if they can prove the eggs themselves are not modified.

MatrixSpec and Ovabrite

MatrixSpec is a Canadian company that is commercializing a technology developed at McGill University originally called Hypereye. Dr. Michael Ngadi, the McGill professor of Bio-resource Engineering that developed the technology, calls the technique ‘Hyperspectal Imaging’ and it combines spectrography and deep learning techniques. They claim to be able to determine gender and fertility pre-incubation, although their accuracy is not 100%. In 2017 it was claimed the technology was 95% accurate before incubation. Whether the accuracy has improved since then is unknown.

Ovabrite is an American company founded as a subsidiary of Vital Farms, an egg-producing cooperative, with technology from Israeli company TERA. TERA uses the terahertz spectrum to detect captured volatile organic compounds that are more difficult to detect with other frequencies. Ovabrite claims their TeraEgg technology can determine gender and fertility before incubation. The accuracy of this technique is unknown.

Both of these techniques work before incubation, although it’s not clear they will reach the accuracy needed to make them viable on a mass scale.

One outlier – Soos

There is one company that takes a completely different approach to the problem of male layer chicks. Soos, in Israel, influences the incubation process employing sound vibrations and adjusting humidity and temperature, causing male embryos to express as females. They can actually change the gender of the bird that hatches only by controlling the environment. The resulting chickens have fully functioning ovaries and can lay eggs with the same efficiency as those that were originally going to be females. With their current implementation, they can influence the gender outcome such that 65% of eggs hatch with females instead of the usual 50%. That’s not a solution to the problem, but it’s definitely thinking outside of the box. If they were able to refine the process to increased accuracy, it could be a very interesting solution since it is non-invasive, takes no additional time, costs virtually nothing, and doesn’t require gene-editing. It would also allow the largest number of female chickens to be born in the same amount of space.

Conclusion

There has been a huge push in the past decade or so to find a solution to the problem of culling male layer chicks. Consumer product companies, industry organizations, and governments alike want to end the practice, but need an economical solution to back.

Unilever committed to end the practice of male chick culling in 2014, but is still hedging on doing so until the technology evolves. United Egg Producers, representing 90% of egg producers in the US, committed to ending the practice in 2016, but had to publish a new statement last year explaining why it hasn’t happened yet. France set a very short deadline in early 2020 to end the practice by the end of 2021, and while there are some culling-free eggs available (the Seleggt eggs using German technology), they have not been able to set an absolute deadline on ending the practice yet.

Like the move from caged to free-range or barn-raised chickens, which is well under way in most countries, it seems inevitable that culling-free chickens will also be required one day. It won’t happen, however, until a good solution is found, proven in real farms, and scaled up so it can be used in farms from small to large. It’s likely that there will be more than one solution to this problem in the long-run, but the first solution to check off all the boxes, particularly related to time and cost, will have the best chance to see widespread adoption. For those working on the technology, there is the added satisfaction that they are contributing towards ending the needless deaths of literally billions of animals a year.